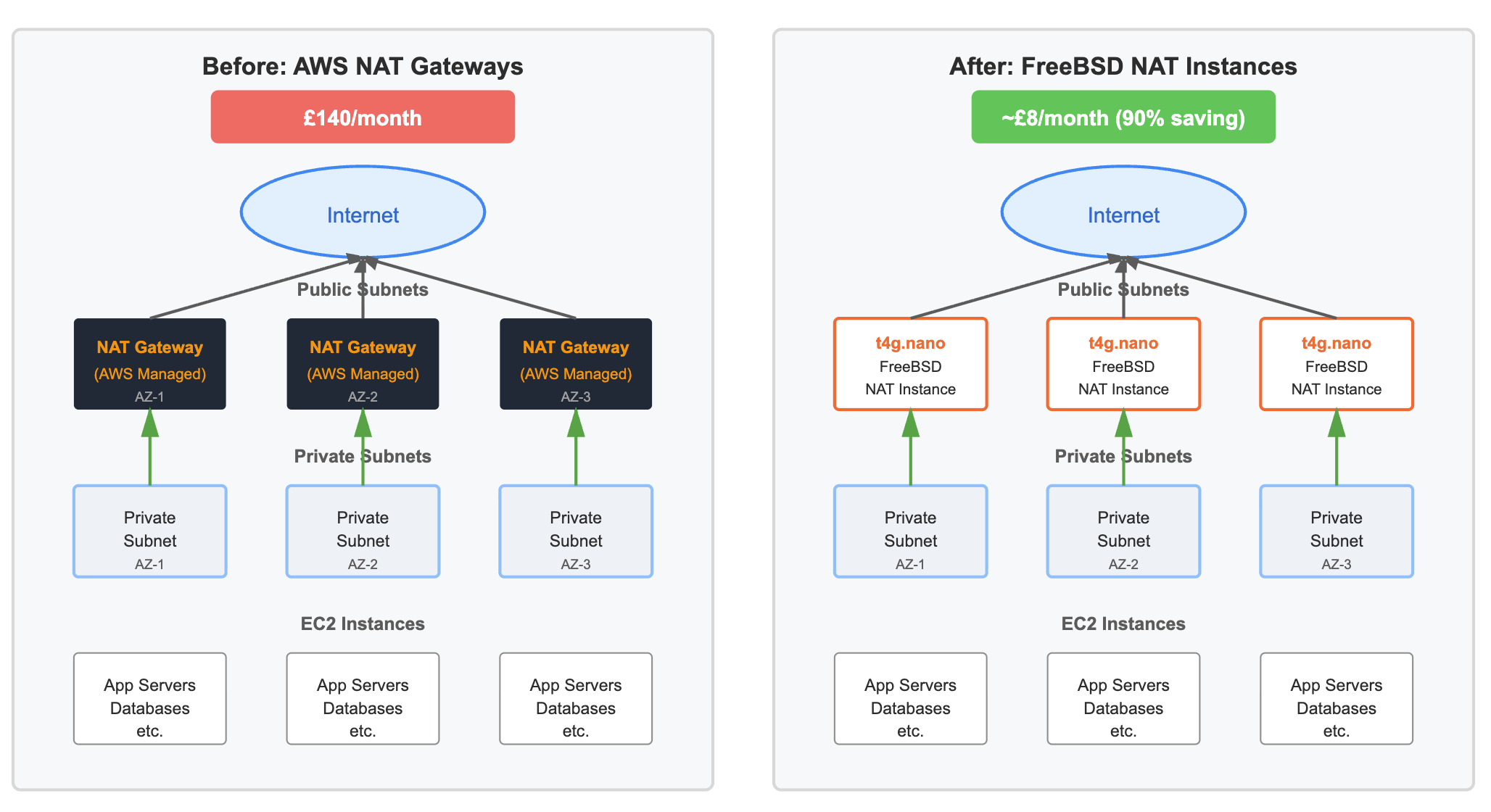

AWS NAT Gateways are frequently treated as a default component of VPC design. They are simple to deploy, highly available, and largely invisible once in place. In multiple Availability Zone environments, the recommended pattern is to deploy one NAT Gateway per AZ and route private subnets to their local gateway. While operationally convenient, this approach comes with a fixed and often under-examined cost.

This post documents an alternative approach: replacing three managed AWS NAT Gateways with three self-managed NAT instances running FreeBSD on t4g.nano EC2 instances. The focus is on the mechanics of the design, the operational behaviour of FreeBSD as a routing platform, and the financial implications of the change.

Baseline architecture: managed NAT Gateways

In the original configuration, three AWS NAT Gateways were deployed, one in each public subnet across three Availability Zones. Each private subnet route table contained a default route pointing to the NAT Gateway in the same AZ. This design preserved AZ locality, avoided cross-AZ data transfer charges, and limited failure impact to a single zone.

For workloads with modest and predictable outbound traffic, this represented a high fixed cost that scaled poorly relative to actual usage.

Replacement architecture: NAT instances on FreeBSD

The replacement architecture mirrors the Availability Zone topology of the managed setup while substituting NAT Gateways with EC2 instances acting as routers.

- Three EC2 instances are deployed, one per public subnet and hence Availability Zone.

- Each instance uses the

t4g.nanoinstance type and runs FreeBSD. - Source and destination checking is disabled at the instance level, allowing the kernel to forward packets that are not addressed to the instance itself.

- Each private subnet route table is updated so that the default route points to the corresponding NAT instance in the same Availability Zone.

From AWS’s perspective, these instances are simply routing targets associated with elastic network interfaces. From the operating system’s perspective, they are minimal edge routers performing IP forwarding and network address translation.

Why FreeBSD

FreeBSD is well suited to this role due to the maturity and predictability of its networking stack and the tight integration between kernel and base system. Routing, packet filtering, and NAT are all part of the core OS rather than layered on via multiple subsystems.

FreeBSD’s PF firewall provides a declarative, stateful model for NAT and filtering with stable semantics. The configuration is concise, auditable, and resistant to accidental complexity. For infrastructure that sits directly on the network edge, this clarity is valuable.

Equally important is what FreeBSD does not include. Compared to general purpose Linux distributions, it exposes fewer kernel interfaces and runtime abstractions. This results in a smaller attack surface and fewer failure modes for a system whose sole responsibility is packet forwarding.

FreeBSD’s conservative release cadence and long-term stability further reduce operational risk for infrastructure expected to run continuously with minimal change.

Configuration walkthrough: turning a FreeBSD EC2 instance into a NAT router

Once a FreeBSD EC2 instance is launched in a public subnet, only a small amount of configuration is required to turn it into a functioning NAT gateway.

The first requirement is IP forwarding. By default, FreeBSD does not forward packets between interfaces. Forwarding can be enabled immediately using sysctl. To ensure the setting persists across reboots, it is added to /etc/sysctl.conf.

net.inet.ip.forwarding=1

The next step is to identify the primary network interface. On EC2, this is typically ena0, which can be confirmed using ifconfig. This interface will be used as the egress interface for NAT.

FreeBSD uses PF for packet filtering and NAT.

PF is included in the base system and does not require additional packages.

PF is enabled at boot via /etc/rc.conf, and its ruleset is defined in `/etc/pf.conf.

To enable PF at boot, the following lines are added to /etc/rc.conf:

pf_enable="YES"

pf_rules="/etc/pf.conf"

A complete and sufficient PF configuration for a NAT instance is shown below:

ext_if = "ena0"

set skip on lo

scrub in all

nat on $ext_if from !($ext_if) to any -> ($ext_if)

pass in all

pass out all keep state

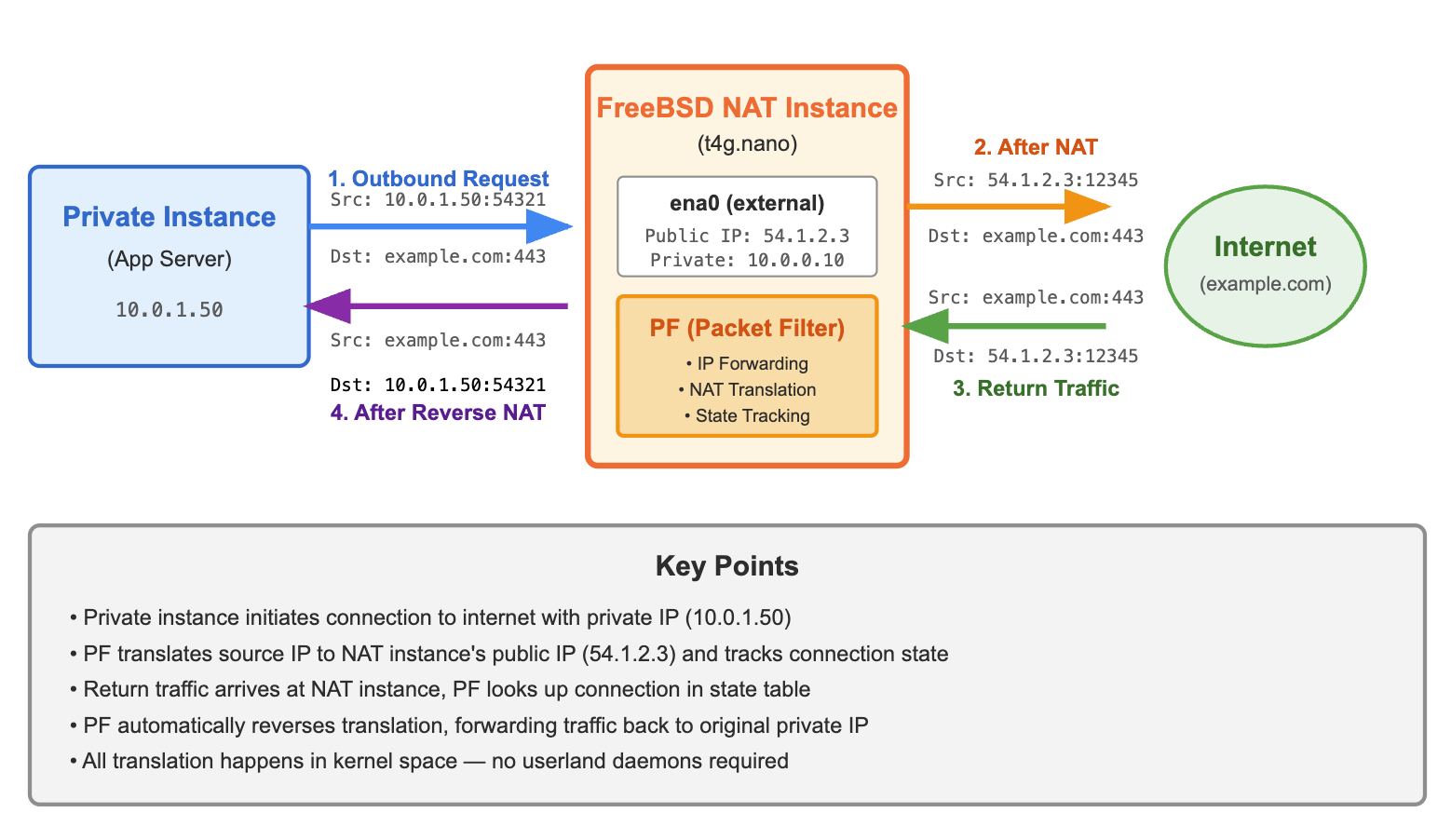

This ruleset defines the external interface, excludes loopback traffic from filtering, applies basic packet normalisation, and performs source NAT on all outbound traffic that does not originate from the external interface itself. The final rules permit inbound and outbound traffic with state tracking, allowing return traffic to flow automatically without explicit reverse rules.

After validating the configuration syntax with pfctl -nf /etc/pf.conf, PF is enabled and the ruleset loaded.

At this point, the instance is fully functional as a NAT router.

All translation and state tracking occurs in the kernel, with no dependency on userland daemons or background services.

With the VPC route tables updated so that private subnet default routes point at the NAT instance, outbound traffic flows transparently through the instance and out to the internet.

Traffic Flow Diagram

Cost and FinOps implications

The financial impact of this change is substantial.

The managed NAT Gateway configuration incurred a fixed cost of approximately £140 per month for three gateways. This cost was independent of actual traffic volume and increased further with per-gigabyte data processing charges.

Conversely, the NAT instance configuration uses three t4g.nano instances. At approximately £2.54 per instance per month, the total monthly cost is around £7.62. Additional costs are limited to standard EC2 data transfer pricing, which is negligible for most outbound-only workloads.

Even allowing for currency conversion and incidental overhead, this represents a reduction of well over ninety percent in NAT-related monthly spend. From a FinOps perspective, this is a clear example of cost optimisation achieved through architectural choice rather than usage suppression.

AWS guidance and the economics of convenience

AWS documentation explicitly recommends NAT Gateways over NAT instances, framing them as the modern, scalable, and operationally safer option. From an operational standpoint, this guidance is understandable. NAT Gateways require no patching, no instance management, no capacity planning, and no operating system level troubleshooting. They are designed to remove responsibility from the customer.

What is far less prominent in that guidance is the cost model. NAT Gateways carry a fixed hourly charge regardless of utilisation, plus per-gigabyte data processing fees. For low to moderate traffic workloads, most of the cost is incurred simply by having the gateway exist.

NAT instances trade convenience for transparency. They require explicit configuration and ownership, but they cost almost nothing to run when appropriately sized. In many environments, the operational overhead of maintaining a small number of dedicated NAT instances is trivial compared to the recurring cost of managed gateways.

More broadly, pricing shapes architectural defaults. When managed services are presented as the recommended option and priced in a way that discourages alternatives, teams are nudged toward convenience-first designs. Over time, these defaults become accepted as unavoidable baselines rather than deliberate choices.

From a FinOps perspective, default does not mean optimal.

It simply reflects the path of least resistance at the time the architecture was designed. Revisiting these defaults as workloads stabilise is often where the largest and least disruptive cost savings are found.

Operational trade-offs

Replacing managed NAT Gateways with NAT instances introduces explicit operational responsibility. The instances must be patched, monitored, and observed like any other EC2 workload. Availability is tied to instance health rather than a fully managed service abstraction. Scaling is bounded by instance capacity, although for typical outbound traffic patterns, a t4g.nano provides ample headroom. I tested a single t4g.nano and found it capable of packet forwarding in excess of 1.25Gbps with no issues.

These trade-offs are intentional. The design favours transparency, simplicity, and cost efficiency over abstraction. For environments with low to moderate outbound traffic requirements, this balance is often appropriate.

Conclusion

AWS NAT Gateways provide a convenient and robust abstraction for outbound connectivity, but they do so at a non-trivial and often overlooked cost. For workloads that do not require their full feature set, small and explicitly managed NAT instances can provide equivalent functionality at a fraction of the price.

By deploying one FreeBSD NAT instance per Availability Zone on t4g.nano, it is possible to preserve AZ locality, maintain deterministic routing behaviour, and reduce NAT costs from approximately £140 per month to under £8 per month.

This approach represents a return to explicit networking primitives and clear operational ownership, with sustained and measurable financial benefit.